Emma Donlan, an inspirational leader from Manchester, always dreamed of changing the world. With a passionate activist mindset and a deep interest in Latin America she pursued a degree in Latin American studies, and for the past 23 years she has been based in La Paz, Bolivia: working as a human rights and social inclusion advisor for international NGOs and the British government.

Currently, she holds the position of Country Director for the Plan International, an NGO that advances children’s rights and equality for girls, leading a large team impacting the lives of over 39,000 sponsored children across more than 600 communities.

Emma Donlan is a true transformational leader, striving to make Plan International in Bolivia more agile, effective, and impactful in the development sector. Her ultimate responsibility lies in ensuring that the needs and proposals of girls and children are always at the forefront of all their efforts, working tirelessly to create positive change and opportunities for a brighter and more equitable future.

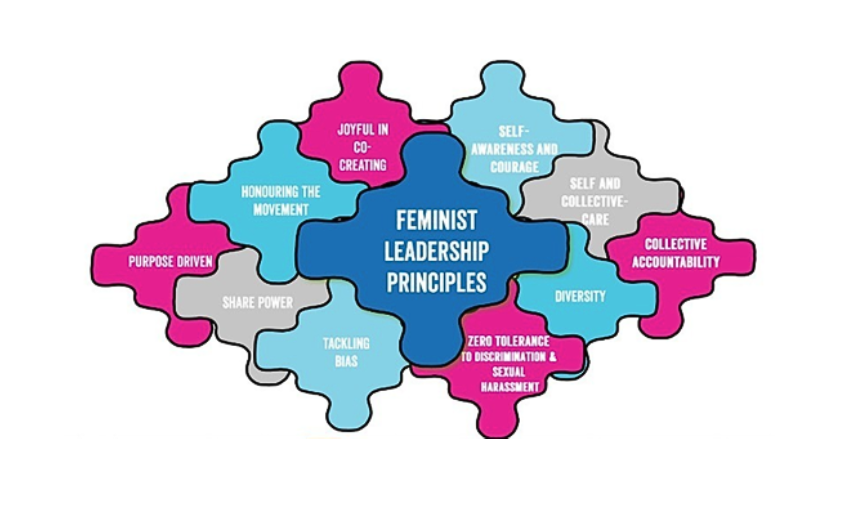

Emma exemplifies her core values through the 10 Feminist Leadership principles.

These principles serve as guidelines, shaping her decision-making and approach to leadership.

However, Emma’s path hasn’t been without its challenges.

When Emma arrived in Bolivia, she encountered leadership styles, deeply rooted in a very patriarchal society that was characterised by traditional hierarchical structures, and a largely ‘machista’ culture. A ‘machista’ culture is a social system that promotes traditional gender roles and male dominance while subordinating and restricting women’s rights and opportunities. For example, when Emma first arrived in South America, she started in a leadership role in an international NGO at only 27 years old. Her expertise was constantly called into question, and many people mistook her for an intern when they came into her office. She was often the only woman in interagency meetings, and she was almost always the youngest person there. The predominantly ‘testosterone-charged’ atmosphere in these spaces felt rather intimidating, as most decisions were made on whoever had the loudest voice.

This situation enabled Emma to develop her own leadership strategies and to build on her strengths in ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking, taking risks, and building alliances to design, propose and deliver innovative projects that presented opportunities for making a greater impact.

Emma had to take a few risky decisions in difficult situations:

For example, she’s had to ensure that the voices of young indigenous people were considered in spaces where decisions were being made that affected them. This meant that she had to challenge adult-centric attitudes that do not value young people’s participation, or even dismiss it entirely. Barriers like these were difficult to overcome, taboos had to be broken, but Emma managed to secure the support of several diverse groups, especially other marginalised groups that had also been underrepresented in these decision-making spaces in the past.

Although Emma has been settled in Latin America for over two decades, she continues to have a ‘backpacker’ mentality.

Her leadership style is characterised by her acute curiosity to understand the diverse experiences and perspectives of the people around her in order to co-construct sustainable solutions that build on, and are rooted in their needs and proposals. People often perceive her as a fresh-faced foreigner, a stereotype she tactfully leverages at times to bridge cultural gaps and build connections. Being a foreigner in Bolivia allows Emma to easily move between social classes and ethnic groups as she doesn’t belong to any specific group herself. Whether she finds herself in ministerial meetings or working in remote indigenous communities in the Amazon, she is greeted warmly and welcomed to share in specific experiences, needs and proposals.

“This mobility is a privilege that truly humbles me and which I try to use to build bridges, broker relationships and overcome tensions or misunderstandings between diverse groups.”

Plan International in Bolivia focuses on three pillars:

- Early childhood: Creating nurturing environments for vulnerable children, particularly girls, challenging gender roles and promoting effective parenting.

- Sexual and reproductive health rights: Empowering young people with knowledge to access to health services, and contraception to address unwanted teenage pregnancies, sexual abuse, and protect adolescent and young women’s rights.

- Economic empowerment: Equipping girls and young women in rural areas with business development tools, fostering self-esteem and independence for their own development.

Additionally, Plan International promotes feminist leadership by educating adolescent boys and girls about equitable relationships and challenging social norms that perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Emma passionately advocates for this cause, empowering adolescents and young men to understand consent and encouraging girls’ assertiveness in decision-making.

As an NGO, Plan International seeks to amplify girls’ voices and the challenge the discrimination harassment they often face in Latin America due to their age and gender. Emma, a dedicated Country Director, prioritises empowering and advocating for the well-being of girls and children in the communities they serve, ensuring the organisation’s values are upheld.

Emma wants to give other women in (aspiring) leadership positions who have struggled to get where they are now a few of her key learnings:

- Ask for help. Something Emma wishes she had learned a long time ago, is that it’s okay to ask for help, it’s okay to admit that you cannot do it by yourself sometimes. Being a leader is about being vulnerable. Courageous leadership involves acknowledging one’s vulnerabilities and seeking guidance from others.

- Acknowledge your privileges and seek ways to share those advantages to empower others. “The best thing a leader can do is to simply listen, step back, and let other people shine.”

- Celebrate diversity. In a society where hierarchical structures still prevail, the need to create a diverse team that represents genders, ages, ethnicities, and other marginalised voices is of the utmost importance.

- Infuse joy and optimism into your work. Given the challenging and emotionally taxing nature of Plan International’s mission, Emma understands like no other the importance of maintaining a positive outlook.

Emma’s leadership journey is one of continuous growth and learning. Her approach resonates with joy, optimism, and unwavering belief in the transformative power of women and girls. Through her leadership, she uplifts and inspires individuals and communities, leaving an indelible mark on their lives. Coming from the Western world with a very forward mindset moving to Latin America where vertical forms of leadership are the norm, there is one thing that inspires Emma the most: Even in completely different cultures than what we are used to, new kinds of leadership are not only possible to realise, but also necessary for the changing world we live in. No matter where you are, you NEED to have authenticity, and you NEED to have the heart and passion to create this new kind of leadership.

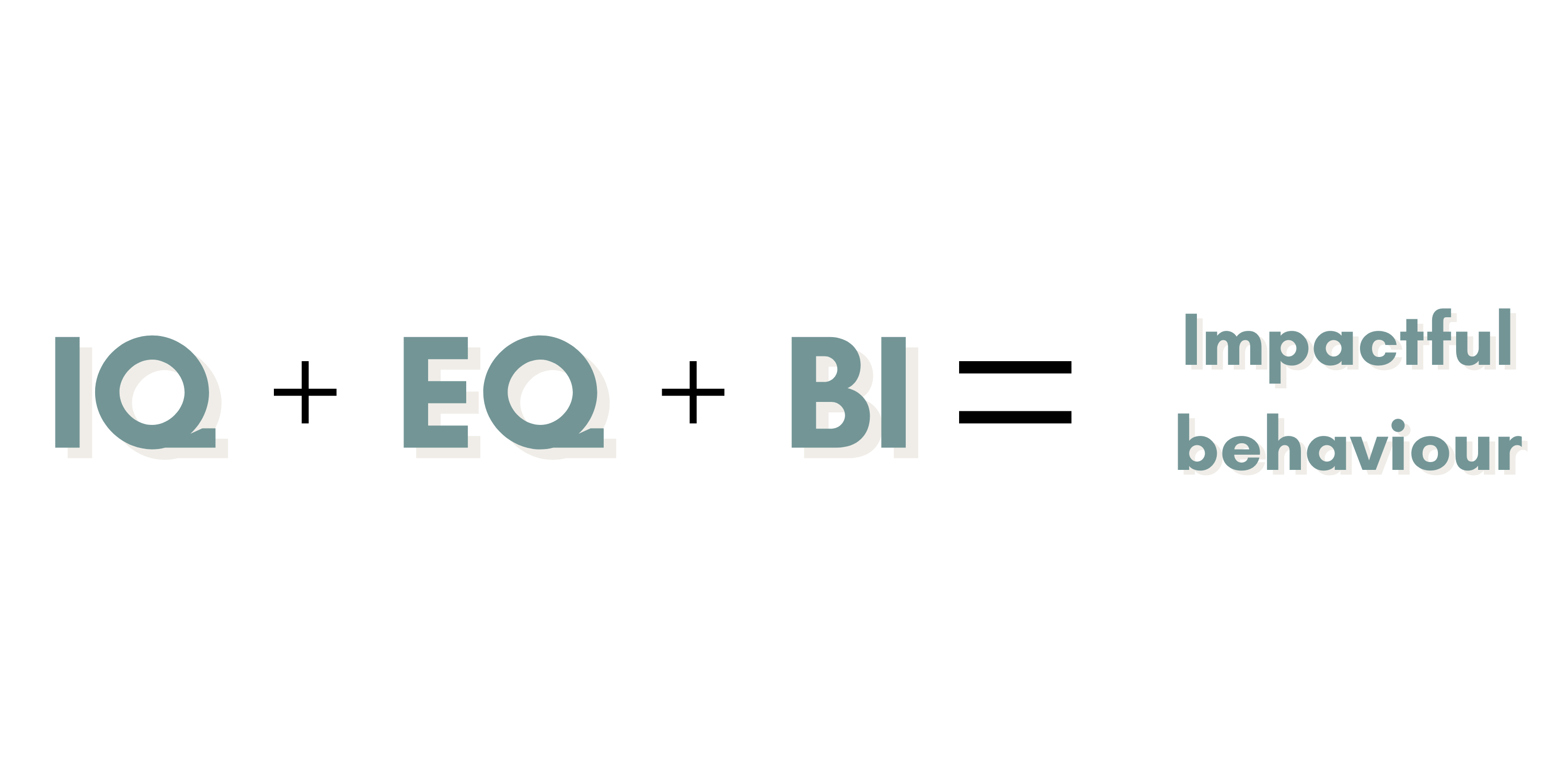

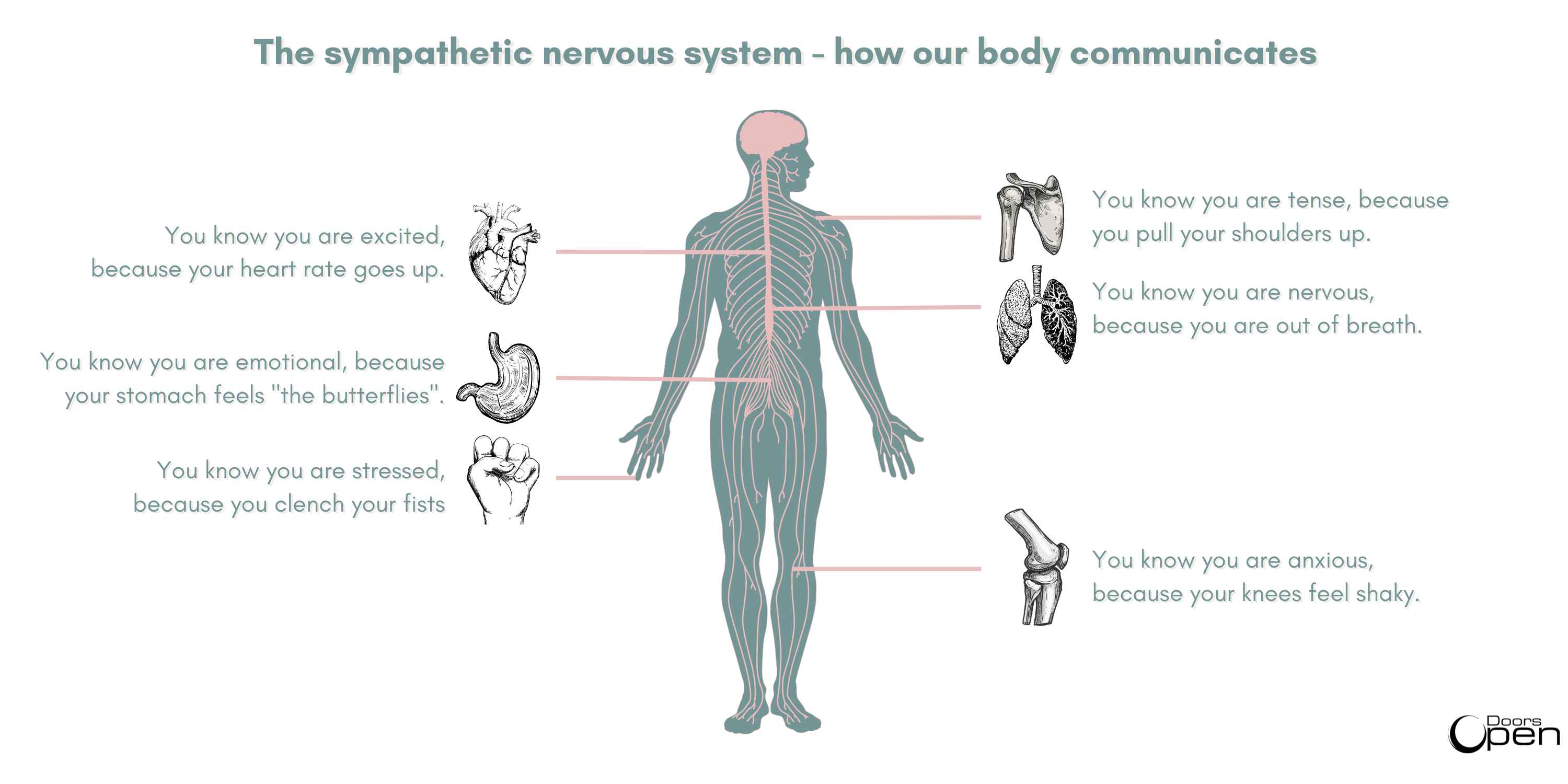

The human connection, the soft skills that we used to think are subordinate, are actually the key to new, effective leadership.

Emma believes leading is about inspiring others.

“If we don’t feel that we’ve made changes in the organisations we work in and in other people’s lives, then what’s the point?”

Emma has never let go of the activist mindset that her 14-year-old-self created, dreaming of changing the world. That idealistic girl is still a part of her, and each time she needs to make a tough decision she just asks herself, “what would 14-year-old Emma do?”. The answer often drives her to be bolder, more intrepid in her course of action, and continue on her life path to make changes that will contribute to a more inclusive and just world, where girls and women are valued, can exercise their rights and reach their full potential.